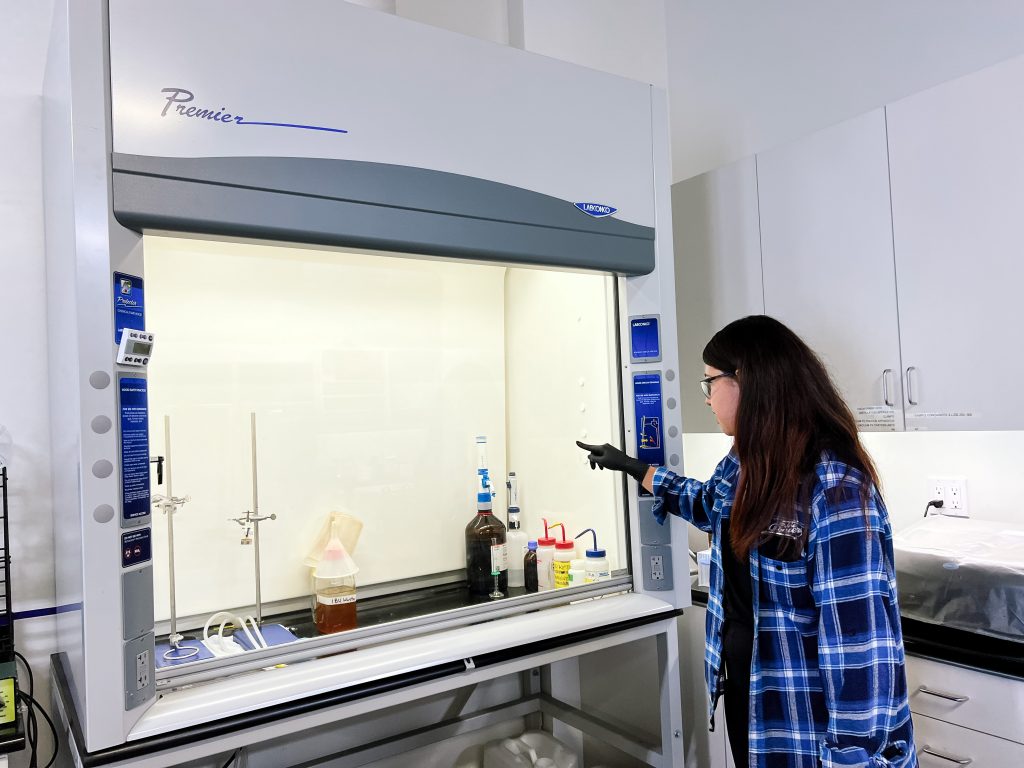

Alex Canales is a Lab Analyst at The Bruery. We met her in the Placentia brewery’s sensory lab, where she is responsible for every area of quality control. On a given day, she’ll perform sensory tastings to check beers for off-flavors, ensure beer is packaged at the proper temperature and total packaged oxygen levels (TPO), and make sure that each beer is what The Bruery calls TTB (or True To Brand).

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

As told to Mark Smolyar and Cambria Findley-Grubb for Hopped.

ALEX: My name is Alexandra Canales and I’m a Lab Analyst for The Bruery in Placentia. My job is basically quality control. I work on every stage in the life of a beer. I’m there beginning from pitching the yeast all the way to packaging our beers. We hold on to a lot of beers from when they were first packaged, up until a few years later, and then we’ll test them and sensory throughout their lifespan to see if they are still worth selling. Or if a customer is holding onto a specific beer, we can test it for them and tell them if it’s OK.

HOPPED: How did you first get your start in beer?

ALEX: I started in the tasting room as a beertender. Before I came to The Bruery, I had worked in a coffee shop. Working in the coffee shop, you get all these cranky customers until they have their coffee, but over here, everyone’s really happy to get their beer. And I was like, “Wow, I love this environment. I want more of it.” People’s faces light up when you talk about the process of beer and go in-depth. Before working here, I wasn’t even a big beer drinker. I liked wine, but I was never a big alcohol person. My interest in beer really came with getting into the nitty gritty of how it’s made. In February 2022, I started as a Lab Technician working in the lab at the Bruery and was recently promoted to Lab Analyst.

HOPPED: What was your background in science before becoming a Lab Analyst?

ALEX: Growing up, I wanted to be a veterinarian, so I decided to learn math and science. I loved it, but very quickly decided I wasn’t going to become a vet. I ended up going to college for chemistry and computer science, which gave me a general lab background. I didn’t really use that experience working in coffee, but even as a beertender, I saw myself using it all the time. I was like, “Wow, I can really use what I went to school for!”

I found even more of an appreciation for science when I started working in the lab here. It was a huge eye-opener for me, learning about the lab side of brewing. My love for science and math was always there, but I think it really blossomed working here.

HOPPED: What was your first experience of drinking craft beer that really impacted you?

ALEX: I think the only beer I was drinking before I started working here was Firestone Walker, because I really loved their products – especially the 805. I could drink that any day. So that opened up the idea of “I like hoppy beers,” and “I like lighter beers.”

When I first started in the tap room, I was blown away by how many beers we had on tap, and how much beer we actually make. Ever since day one, my favorite beer we had on was Mischief, our Hoppy Belgian-style Ale. There is a tiny bit of a spice to it with black pepper notes. From there, I realized, “I love Belgians.” Belgians are not a super popular style, but I think when it’s done right, it’s amazing. I think that Mischief was such a pivotal thing for me because I’d never had a craft Belgian before, and now I still love them.

HOPPED: How did the beers at The Bruery really help define your palate?

ALEX: Working as a beertender, your main job is to sell the product, and when you sell a product you have to know what you are talking about. So I would taste every new beer we had. If we had 40 beers, I tasted all 40 of them. That really helped me develop my palette. I very quickly started to realize I was not an IPA person. I definitely loved lagers, pale ales, and then sours. I never had a sour before working here. The first sour I ever had is still to this day my favorite beer. We made a Rum Barrel-Aged Tart of Darkness with cherry and vanilla, and it literally tastes like you’re drinking a rum and cherry-vanilla coke. From there, I started going from darker sour stouts into actual stouts. However, that can be dangerous because we love to make high-ABV stouts.

I have a huge sweet tooth so I tend to go more for the sweeter beers. We made a beer once called Portfied Black Tuesday, aged in French oak barrels with small hints of vanilla. It was all about the barrel character and it was to die for.

HOPPED: Tell us a bit more about how working as a Beertender impacted your experience before moving to the lab?

ALEX: Starting in the taproom, everyone we had working around me was incredibly knowledgeable. We had some beertenders in their seventh or eighth year. They’d seen everything The Bruery had gone through, and a lot of my knowledge came from them. People made sure I knew that if I had a question, I didn’t hesitate to ask. And that’s exactly what I did. I’m the type of person who can’t just stick with an answer and not know the “why” behind it. So I got to know the brewers really well every time they would come and have their shift beer. Also, when I started, I was provided with lots of materials because I wanted to expand my knowledge. Then when I made the switch to working in the lab it was like, “It’s going from zero to 100, here we go.”

HOPPED: What was it like making the switch from behind the bar to in the lab?

ALEX: Working in the lab, I realized I didn’t know as much as I thought I did. Anything from brite tanks, to mechanical things, to yeast, anything that you can think of that is beer related, I learned it in the lab, and it definitely took awhile. And I still don’t know every single detail. So I’ve been in the lab for seven months, and I feel like I’ve learned more in seven months than I have in my entire time being at The Bruery, which is crazy!

I didn’t even know The Bruery had a lab when I first started working here, but you meet a lot of coworkers when they stop by for a beer after their shift. One of the previous lab workers was awesome and would always come by after work and talk to me about what she did, and that’s how I learned about the lab. It was so cool to hear how what I used in college could be used here. But she was only here temporarily because she was going to be leaving to pursue teaching. She’s the one who told me I should apply. I am so happy they even gave me the opportunity because this has been hands down the best job I’ve ever had in my life.

When I started, there was definitely a lot of information thrown at me. I didn’t realize it on day one, but I am everywhere in this entire facility. I thought I was going to be in the lab the whole time. No, you’re out and about, you are everywhere. I had been out of school for about four years, so it had been awhile since I had touched anything science-related. But my coworkers were so patient and they made it very comfortable and easy. I would ask the same question 10 or 20 times, so if it wasn’t for their patience I would have struggled because of how much we do here and how much there was to learn.

HOPPED: What does a typical day look like for a lab analyst?

ALEX: Typically I work from 6:30am to 3pm, the main reason being that we start packaging very early. We package both cans and bottles, but regardless, the first thing our sensory-trained team has to do is taste the beer. I don’t drink coffee first thing in the morning because it affects my palette. When we perform a sensory, we’re making sure that it’s true to brand, or “TTB”. We’re smelling and tasting it to catch any off flavors, pinpointing the ingredients in the beer, and also checking if the carbonation is at a good level for the beer. The tools we use to get readings on the beer can be inaccurate, so it’s important to trust your senses and go with your gut.

HOPPED: What does it mean to be sensory trained?

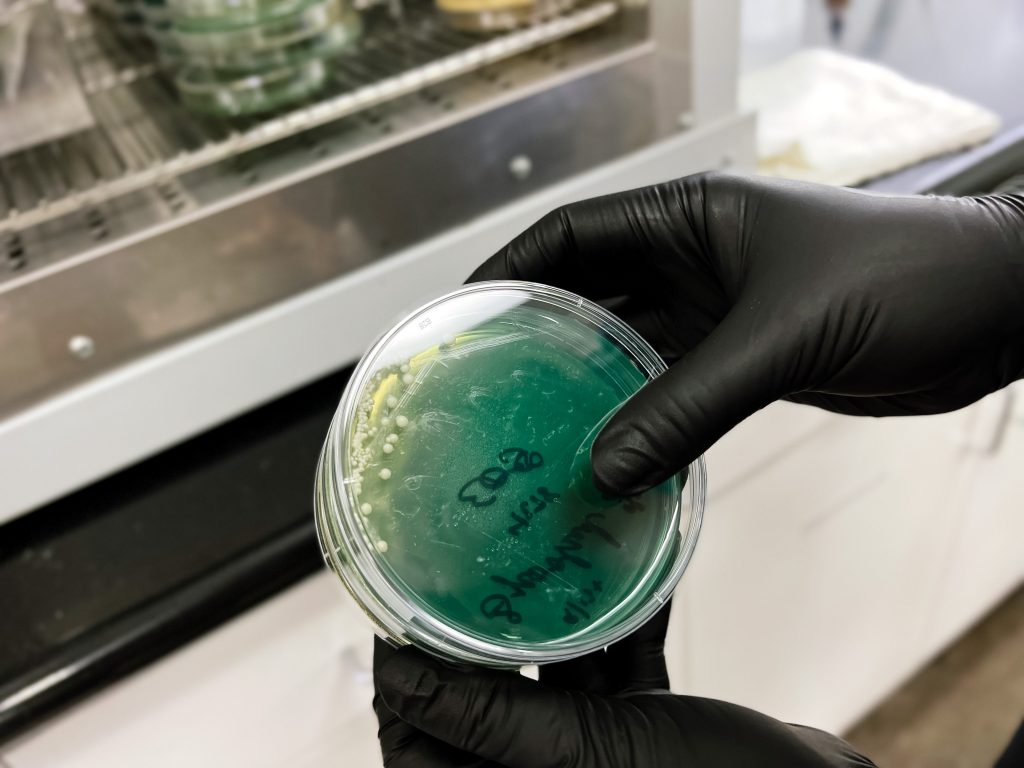

ALEX: We have a team of approved individuals who have all been trained to appropriately find off flavors in beers. As part of our training, we have these little capsules of all the different off-flavors that happen in a beer. Then we’ll grab one of our beers, like Relax from [The Bruery sibling brewery] Offshoot, and set up three tasters, where one of them is dosed with the off-flavor and the other two are not. We then train brewers, the production team, or leads, everyone who is involved in the production process, to look for that off-flavor. Sensories are a really big part of our work and I appreciate that we do them.

We need at least three sensory-trained individuals to sign off on every beer we brew. But sometimes we’ll get those moments where it’s 50/50 – some people catching off flavors and others not – so it’s important to know what you‘re looking for. When we get one of these splits, we get my boss involved, who is the Head of Quality Management – he has the final sign-off on everything. Worst case, if a beer’s not good, we’ll dump it if there’s no way to save it. Sometimes you don’t have a good brew and it sucks, but it happens. We take the idea of being true to brand and quality very seriously.

HOPPED: What happens after morning sensory?

ALEX: A major priority for my job is packaging, so I’m working with the packaging team to make sure everything is hooking up correctly. I’m an extra set of eyes and ears to make sure that everything is functioning the way it should be, and being prepared the way it should be. This summer was super hot, so a lot of my job was making sure that our beers were at an adequate temperature to package. There are a lot of little adjustments you make and we have a big database that tracks all of our numbers from every packaging we’ve ever done. So, part of my job is to look at previous data to see how it looks compared to the current packaging, such as the oxygen levels. If they were good, then I’ll take the data, which has notes about what the machines were set to, and replicate it. I’m a perfectionist, so I always want to know how we can make something better. We also do checks every hour, so within that time frame, I’ll go back to the lab, run any samples that have been collected from a fermenter stage, or a final brite tank stage, or a crash sample so I can run them simultaneously.

Later in the day, I’ll start to read my color and IBUs for beers. Another task I work on relates to letting brewers know if a beer is ready to crash [beer speak for chilling a beer near freezing after fermentation and before packaging]. We use data from fermentation logs to see if the gravity is stable enough for a beer, and then additionally use a Vicinal Diketones test to see where the beer is at in its current stage. As long as it falls within the necessary range for that particular style, you can let the brewers know that their beer is ready to crash. If the beer isn’t ready, we’ll test it again in a couple of days.

We have a specific room designed for our spontaneous fermented beers. Three weeks is usually as much time as the beers need to fully ferment and fully carbonate. With those beers, the only way we can control them is through the set temperature in the room. We like to spontaneously ferment because we are spontaneous people. We like trial and error and we like to take risks. It’s definitely a love-hate relationship, especially working in quality control, because your job is to be able to control everything you can, but there is always room for error. For us, we learn where we messed up so we can prevent the problem in the future.

HOPPED: Have you worked on the brewing side?

ALEX: I don’t see myself doing a lot of brewing, but I like being involved. I like creating beers and coming up with ideas and I have enjoyed brewing, but I think I’m just way more interested in the science of everything than I am in the actual physical experience of doing so. That being said, I did just help brew a beer for the 14th anniversary. It was a Belgian Table Beer called ‘Hips Don’t Lie’ made with rose hips. I am a part of OC Pink Boots (a national nonprofit dedicated to supporting women in the alcoholic beverage industry through education), and it was a big collaboration that we did. Throughout the process, I was working collaboratively with our brewing team. In the majority of cases about making a choice with a beer, it really isn’t entirely my call when it comes to the beer itself. But when it came to something like, “Hey, I’m seeing there’s a fluctuation of that change of energy with this beer or we pitched this beer, but that pH was really high or really low, what could be wrong”, that’s when I step in to be like, “Okay, well, let’s break this down. What actually happened? Oh, is it maybe one of our pH meters that’s just reading incorrectly? I can totally fix that, no problem.” Maybe in another year or two, I will be able to make some of those other calls, but at least for right now I’m still more in the “I’d rather train as much as I can and learn as much as I can” mode.

HOPPED: What advice do you have for women who are interested in getting involved in the beer industry?

ALEX: I think my biggest piece of advice is to never stop asking questions. Honestly. I feel like if I didn’t do that, I wouldn’t be where I am today. I used to be a lot more reserved. If people told me something, I would just accept it. I quickly learned that in this industry, at least specifically at The Bruery, they’re very open to everyone: ideas, questions, comments, concerns, literally anything. And I feel like it’s kind of the first place that I had that sense of respect and that sense of an opportunity for me to actually speak my mind. And I feel like that should be everywhere. So my advice to women is to just keep speaking your mind and if you want something, go for it because no one’s going to just hand it to you. I feel like I had a lot of open doors just working as a bartender and never thought I was gonna be working in the lab, but here I am.

Cambria Findley-Grubb

Cambria Findley-Grubb Mark Smolyar

Mark Smolyar